Gainful Employment Rules and School Closures (2014–Present) – MAY 2025 STUDY

Gainful Employment (GE) regulations were introduced in the Obama era to ensure career-training programs lead to “gainful employment” for graduates. The 2014 GE rule set debt-to-earnings benchmarks that programs had to meet or risk losing access to federal student aid. Many for-profit and vocational programs—particularly in cosmetology—performed poorly under these metrics. In fact, roughly 32% of cosmetology certificate programs failed or were in a “warning” zone under the 2014 GE debt-to-earnings tests, compared to about 24% of programs overall. Hundreds of programs (notably in beauty and medical assisting fields) fell short of the standards, and some institutions closed as a direct result of these regulations. For example, Regency Beauty Institute shuttered all 79 campuses in 2016; its owner cited declining enrollment and the new GE rules – which threatened access to federal aid – as key factors in the decision. Similarly, Marinello Schools of Beauty, a chain of 56 campuses, lost Title IV eligibility in 2016 due to federal findings of fraud and subsequently closed, leaving over 4,000 students in the lurch. These are among a wave of mid-2010s for-profit closures (e.g. Corinthian Colleges in 2015; ITT Technical Institute in 2016) that were spurred by stricter oversight, including GE rules, loan default sanctions, and accreditation crackdowns.

After 2014, the gainful employment regulations proved contentious. The rule was rescinded in 2019 under the Trump administration, pausing enforcement. However, in 2023 the U.S. Department of Education revived and strengthened the GE framework, finalizing new regulations to take effect by 2024–2025. The updated rule again requires career programs at for-profit colleges (and non-degree programs at any school) to show that graduates can repay loans and earn above the median high school graduate’s wage, or else lose federal aid eligibility. This pending implementation has raised alarms in the beauty school sector, which disproportionately relies on federal student aid. In late 2023, the American Association of Cosmetology Schools (AACS) filed suit, arguing the new rule would “jeopardize the very existence” of many cosmetology programs. In essence, the schools admitted that if forced to meet basic debt and earnings benchmarks, many would likely fail and shut down. This underscores what happened in the previous GE era: poorly performing programs either must improve outcomes or face closure. Indeed, federal data from the last GE implementation showed that cosmetology programs were disproportionately failing; out of about 1.9 million cosmetology students and licensees in a given year, a large share had debt-to-income ratios that flunked the standard. The Biden administration has stood by the rule as necessary to protect students and taxpayers from “programs known to leave graduates with unaffordable debt and poor career prospects”. As of 2025, the GE rule is slated to roll out, and we are already seeing smaller for-profit cosmetology schools closing or bracing for impact. For example, Health & Style Institute (a beauty school with campuses in NC and GA) abruptly closed in early 2024 with little notice, stranding students – an outcome attributed to financial stress and the challenging regulatory environment (though not explicitly labeled a GE failure, it illustrates the instability in the sector). Going forward, any program that consistently leaves graduates with low earnings relative to debt is at risk. In short, since 2014 gainful employment regulations have contributed to numerous school closures, and the post-2023 resurgence of these rules is expected to intensify pressure on for-profit vocational and beauty schools, likely resulting in further shutdowns of programs that cannot prove real employment value.

Impact on Beauty Schools and For-Profit Vocational Institutions

For-profit beauty colleges have been among the most affected by these accountability measures. Cosmetology and related programs often serve low-income students who borrow federal loans to cover tuition; as a result, the entire beauty school industry has been fueled by federal aid dollars (about $2.2 billion annually). Unfortunately, many graduates see meager earnings. Federal analyses have found that many cosmetology graduates earn no more than a high school graduate, despite taking on student debt. In the mid-2010s, when the GE rule first took effect, this reality translated into failing scores for a large number of beauty programs. Schools that lost Title IV eligibility had little choice but to shut down. Regency Beauty Institute’s 2016 closure was one of the largest, directly citing the gainful employment rule’s threat to its federal funding. That same year, Marinello Schools of Beauty abruptly closed all campuses after the Education Department moved to cut off aid over “pervasive and egregious” regulatory violations. And beyond cosmetology, other for-profit vocational institutions were collapsing as well: Corinthian Colleges (Everest, Heald, Wyotech) closed in 2015 under the weight of fraud allegations and GE-related loan discharge liabilities; ITT Technical Institute folded in 2016 after losing accreditation and aid access; Education Corporation of America (Virginia College, Brightwood) shut down in 2018 amid financial and compliance troubles. In total, well over a thousand for-profit campuses have closed since 2014, a trend closely tied to stricter federal oversight like the GE regulations and enforcement of loan default rates.

Beauty and cosmetology schools form a significant piece of this trend. Not only did they lobby heavily against the 2014 rule, but they also suffered many of the rule’s consequences. Recall that nearly one-third of cosmetology programs nationwide failed or nearly failed the 2015–2017 gainful employment tests, a far higher fraction than most other fields. This poor performance reflects underlying issues: low on-time graduation rates, licensing hurdles, and saturated job markets. In some cases, state authorities and accreditors began taking action as well. For instance, in 2024–25 a prominent Paul Mitchell beauty school in Tennessee faced loss of accreditation due to financial instability and was slated to close – even before the new GE rule hit – because it had only a 3% on-time graduation rate and abysmal loan outcomes. Regulators increasingly recognize that many of these programs leave students worse off. A recent investigation noted that at one Paul Mitchell cosmetology campus, 60% of graduates earned no more than a typical high schooler (only 40% exceeded a high-school income), and over half the students were unable to repay their loans (many stuck in forbearance or default). These kinds of outcomes are exactly what GE metrics are designed to spotlight. The post-2023 landscape is one where beauty schools either improve outcomes or risk closure. AACS itself admitted in court filings that many member schools would go under if forced to meet the new standards. Thus, we are likely to see more closures after 2023 as the rule is implemented – essentially a culling of programs that “leave students no better off” in terms of earnings. The intended national impact is to protect students, but the side effect is a contraction of the for-profit vocational sector, especially in cosmetology, where numerous programs have been of questionable value.

Short Programs vs. Cosmetology: Employment and Entrepreneurship Outcomes

How do shorter programs (e.g. Nail Technology or Esthetics) compare to longer cosmetology programs in job placement and business ownership? Intuitively, shorter specialty programs require fewer training hours (often a few hundred hours, versus 1,000–1,500+ hours for a full cosmetology course) and typically cost less, which can translate to lower student debt and a quicker path to employment. In recent years, some states have even moved to reduce cosmetology hour requirements (for example, Iowa cut its requirement from 2,100 to 1,550 hours in 2023, and Texas down to 1,000 hours) with the aim of removing unnecessary barriers. These shorter pathways can improve completion rates and get graduates into the workforce faster. Placement data from schools and accreditors suggest that specialized programs often achieve placement rates comparable to, if not better than, general cosmetology. For instance, one beauty academy’s disclosures (in Utah) showed a ~75% job placement rate for its Nail Technician program – on par with or above the typical placement rates for cosmetology graduates (which might hover around 60–70% in many schools). Short programs tend to be laser-focused on a specific skill (nails, skincare), and the industries for these services (nail salons, spas, etc.) have been growth areas. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects employment of manicurists and pedicurists to grow about 22% from 2021 to 2031, much faster than average. Skincare specialists (estheticians) are similarly expected to grow ~11–17% over the decade. By contrast, the broader category of hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists is projected to grow around 7–8% in the same period. This indicates strong demand for the specific services that shorter programs train for, potentially translating to more job opportunities for those graduates.

Salon ownership and self-employment are common in the beauty field across the board, but data show some differences by specialization. According to BLS-derived statistics, about 51% of hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists are self-employed (often renting booths or owning salons). Nail technicians and skincare specialists also have high rates of self-employment, roughly 30% or more in those occupations. In other words, a significant portion of graduates in all these programs eventually work independently. Cosmetologists, with their broader skill set, often have the flexibility to offer a range of services and are quite likely to start their own full-service salons or work as freelance stylists – over half are essentially their own boss. Nail techs and estheticians, while sometimes opening boutique studios, more frequently work as employees in spas or nail salons early in their careers (the self-employment rate for manicurists is ~30%, which is lower than for cosmetologists but still higher than many occupations). Overall, shorter program grads appear to do at least as well – and often better – at securing jobs quickly, due to the focused demand for their skills. Their entrepreneurial outcomes are strong too, though not dramatically higher than cosmetologists in a proportional sense. If anything, all sectors of cosmetology encourage entrepreneurship: for example, many cosmetology programs (like the one at Ms. Roberts Academy in Illinois) include coursework on salon management, marketing, and how to start a business, reflecting that opening a salon or boutique is a common aspiration. In summary, graduates of nail technology and esthetics programs tend to have solid job placement rates and can often find work immediately in their niche, avoiding some of the oversupply issues plaguing general cosmetology. They also participate in the industry’s high rate of self-employment – roughly one-third of nail and skin specialists, and over one-half of cosmetologists, end up working for themselves in some capacity. There isn’t clear evidence that, say, 100-hour nail tech grads are more likely to become business owners than 1,000-hour cosmetologists; rather, all short and long programs in beauty yield a high level of entrepreneurship. The key advantage of the shorter programs is that students invest less time and money up front, which may lead to better ROI and possibly higher completion and licensing rates, enabling them to enter the job market (or start a business) with less financial burden.

New Policies: Shifting Federal Funding Authority to States?

Historically, to receive federal student aid (Pell Grants, loans, etc.), a school must be accredited by an agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. Accreditation has served as the gatekeeper for federal funding – a quality check to ensure institutions meet baseline standards. Recently, however, there have been proposals and policy moves to reform this system, potentially giving states more say in which schools can access federal dollars. Notably, in April 2025 a Presidential Executive Order on Higher Education Accreditation Reform was issued, criticizing accreditors for acting as “gatekeepers” that have “failed in [their] responsibility” to ensure educational quality. This order (one of several targeting higher ed) directs the Education Department to overhaul the accreditation process, in part because of concerns that accreditors focus on wrong priorities. While the executive order’s full implications are still unfolding, its Purpose section explicitly notes that accreditors hold “enormous authority” over what colleges can receive funds, and it condemns them for letting low-quality programs slip through while “intrud[ing] on State and local authority” in other ways. The reform effort is expected to hold accreditors more accountable and possibly reduce their monopoly on approving schools. One idea floated in policy circles is to allow alternative paths to Title IV eligibility, such as state authorization or new forms of accreditation. For example, a state government (or its designated agency) might be empowered to determine that certain licensed vocational schools provide sufficient quality and therefore should be eligible for federal aid, even if those schools lack traditional accreditation. If such policies were implemented, it could mean that any state-licensed postsecondary school (e.g. a small beauty academy licensed by the state cosmetology board) might tap into federal student aid regardless of accreditation status. In essence, the funding gatekeeper role would shift toward the states. This concept has been championed by some for-profit education advocates and lawmakers who argue that the current accreditation system is a barrier to innovation and competition. It’s important to note, however, that changes of this magnitude would likely require Congressional action or major regulatory overhaul, since the Higher Education Act presently mandates accreditation for Title IV institutions. As of now (2025), we are seeing initial steps: the Department of Education has indicated interest in aligning federal aid eligibility more closely with state oversight in certain areas. One concrete example is a new rule to stop schools from dramatically exceeding state training requirements: the Department found that some cosmetology programs were 50% longer than required for licensing, thus costing students more tuition for little added benefit, and moved to bar programs from billing federal aid for hours beyond the state-mandated minimum. By tying allowable program length (for federal aid) to state licensure standards, the federal government is effectively deferring to states’ judgment about how much education is necessary for a given trade. This policy shift strengthens the role of state authorities in policing program value and could pressure schools to trim excessive curricula. There are also bipartisan discussions in Congress around “short-term Pell” grants for non-degree job training, which would rely on states and quality-control metrics to approve programs – another avenue by which state agencies might determine aid eligibility for programs outside the usual accreditation system.

In summary, current and proposed policies are indeed inching toward greater state influence over federal funding decisions. The Executive Order on accreditation reform signals a push to “reform our dysfunctional accreditation system”, potentially allowing new accrediting entities or even direct state approval to replace the old model. If such reforms succeed, it could open the door for all state-licensed schools to access Title IV aid regardless of traditional accreditation. Practically, that means a small licensed cosmetology or barber school, even if not accredited by a U.S. Dept. of Ed.–recognized agency, could become eligible for federal student aid if the state deems it satisfactory. Proponents say this would expand student choice and reduce regulatory burden on niche vocational schools. However, critics caution that removing the accreditation gatekeeper might invite low-quality or even fraudulent schools to misuse federal funds, repeating past scandals. It remains to be seen how far the Administration and Congress will go – the Department of Education would have to pilot alternatives carefully, and statutory changes to the Higher Education Act would likely be needed to fully remove the accreditation requirement. At present, no blanket policy has opened aid to all state-licensed schools, but the trajectory is toward flexibility: aligning programs with state standards (as with limiting cosmetology program hours for aid) and re-examining accreditor power. We can expect ongoing debates on whether states should have the authority to determine aid eligibility. If implemented, such changes would indeed broaden the pool of schools eligible for federal aid, giving many unaccredited, state-approved vocational schools a chance to enroll students with Pell Grants or loans – a prospect greeted with both optimism and concern in the education community.

Are 75% of Licensed Cosmetologists Unemployed?

There is a frequently cited statistic that “75% of licensed cosmetologists are not working in the field.” While the phrasing can be misleading, there is data to substantiate a very high non-employment rate among cosmetology license holders. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and other analyses have long shown that far more people graduate from cosmetology programs (or hold cosmetology licenses) than the labor market can absorb. The result is a huge number of licensed cosmetologists who end up in other occupations or economically inactive in this field. A federal Office of Inspector General report once highlighted this oversupply: in 1990, about 96,000 new cosmetologists were trained in the U.S., adding to an existing pool of 1.8 million licensed cosmetologists, yet only 597,000 were actually employed as cosmetologists in that year. That means roughly 30% were working in the occupation and about 70% were not (unemployed in the field or working elsewhere). This 70% figure is in line with the “75%” claim. In other words, only about one in three licensed cosmetologists at any given time is working as a barber, hairstylist, or cosmetologist; two-thirds or more are not employed in jobs requiring their cosmetology training. This startling ratio was noted decades ago and remains relevant. The New America Foundation’s 2025 report on cosmetology education cites these labor market dynamics, underscoring that the market has been completely oversaturated for years. It is important to clarify that this does not mean 75% of cosmetology graduates are formally counted as “unemployed” (in the general sense of seeking work and unable to find any job). Rather, many licensed cosmetologists simply leave the profession or never enter it, often because they cannot secure a decent-paying job in the beauty industry or find the working conditions unfavorable. They may work in other fields or drop out of the workforce for a time. For example, new graduates often struggle to build a clientele and may take up different jobs, leading to high attrition from the sector within a few years of licensing.

Contemporary BLS data reinforce the point: as of 2023, there were approximately 649,000 jobs for hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists in the United States. Meanwhile, the number of individuals holding active cosmetology licenses is easily in the millions (states collectively have issued licenses well above that job count). So it is accurate to say a large majority of licensed cosmetologists are not employed as cosmetologists at any given time. In casual terms, one might say “about 3 out of 4 licensed cosmetologists aren’t working in salons” – hence the 75% figure. Official statistics from a 1990 BLS survey found roughly 69% of licensed cosmetologists were not employed in the field, and while we don’t have a precise updated percentage, industry experts believe the situation today is similar. In fact, the chronic oversupply of practitioners is a major reason regulators and legislators have considered trimming educational requirements (to not flood the market) and why gainful employment rules target cosmetology programs – because so many graduates fail to find sustainable employment.

In summary, yes, data show that on the order of 70–75% of people with cosmetology training/credentials are not currently working as cosmetologists. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are all unemployed in the general sense – many pursue other careers – but it does highlight a serious disconnect between the number of beauty school graduates and the available jobs. The profession’s employment rate (for those with licenses) is extremely low. From the standpoint of labor outcomes, that statistic is a red flag: it implies that far too many students are being trained for jobs that simply don’t exist for all of them, one more reason the Department of Education and some states are pushing for reforms in the cosmetology education arena.

Sources:

- U.S. Department of Education, Gainful Employment regulations and notices

- Inside Higher Ed – Paul Fain, “Beauty School Chain Closes Abruptly” (Regency Institute closure and reasons)

- Inside Higher Ed – Quick Takes (Feb 2016), “For-Profit Closes After Losing U.S. Aid” (Marinello Schools of Beauty closure)

- New America (Jeremy Bauer-Wolf et al.), “Cut Short: The Broken Promises of Cosmetology Education” (2025 report on cosmetology outcomes and industry)

- Republic Report (J. Bauer-Wolf, 2025), “How Cosmetology Education Cuts Students’ Dreams Short” (AACS lawsuit admission and industry statistics)

- American University, “Hair and Taxes: Cosmetology Programs and Underreported Income” (Stephanie Riegg Cellini et al., 2020) – analysis of GE data showing 32% of cosmetology programs failed or near-failed GE metrics.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics – Occupational data for Cosmetologists, Manicurists, and Skincare Specialists (employment numbers, growth rates, self-employment rates).

- Executive Order “Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education” (Apr 23, 2025) and related fact sheets, as reported by the White House and policy analysts.

- New American Business Association (NABA) analysis, “The True Cost of Education Access: …Vocational Schools” (Mar 2025) – discussion of federal/state roles in funding and accreditation.

Summary: Evidence Supporting Shorter Beauty Programs Over Cosmetology

Shorter Programs (Nail Tech & Esthetics) Outperform Cosmetology in Employment, Affordability, and Return on Investment

1. School Closures Linked to Gainful Employment Rules

- Over 1,000 for-profit institutions, including major beauty school chains (e.g., Marinello, Regency), closed since the implementation of the 2014 Gainful Employment (GE) rule.

- Cosmetology programs disproportionately failed GE metrics: ~32% of programs were flagged as non-compliant.

- DOE and courts acknowledged these programs often lead to unaffordable debt with low earnings.

- Closure trend is expected to intensify with the 2024–2025 GE rule reinstatement.

2. Employment Outcomes: Cosmetology vs. Shorter Programs

- Cosmetology:

- Requires 1,000–1,500 hours of training.

- Employment rate: Only ~30% of licensed cosmetologists are working in the field.

- ~70–75% of license holders are not employed in cosmetology jobs.

- Oversaturation of market and high debt burden noted.

- Nail Technology (450 hrs) & Esthetics (750 hrs):

- Job placement rates: ~75% or higher in some states and schools.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS):

- Nail Tech growth: 22% projected 2021–2031.

- Esthetics growth: 11–17% projected.

- Cosmetology growth: ~7% projected.

3. Salon Ownership & Self-Employment Trends

- Cosmetologists: ~51% are self-employed.

- Nail Techs/Estheticians: ~30–35% self-employed.

- All beauty programs foster entrepreneurship, but shorter programs allow faster entry into ownership due to lower debt.

4. Lower Cost, Faster Payoff with Shorter Programs

- Shorter programs cost significantly less (~$5K–$10K total).

- Graduates can repay loans in months, not years.

- Programs like Nail Tech and Esthetics can be completed in 3–6 months.

5. Current DOE Reforms and State-Level Shift

- April 2025 Executive Order targets accreditation reform and increased state oversight.

- Federal rules now limit aid eligibility to program hours not exceeding state license minimums.

- Policy direction is shifting toward state-approved aid eligibility without federal accreditation.

6. Policy Recommendations

- Federal aid should be open to all state-licensed programs, especially short ones, without requiring costly accreditation.

- Aid should follow students based on licensing goals—not arbitrarily tied to 600+ hour programs.

- Programs with high job placement and proven ROI (like Nail Tech & Esthetics) should be prioritized.

7. Call for Action

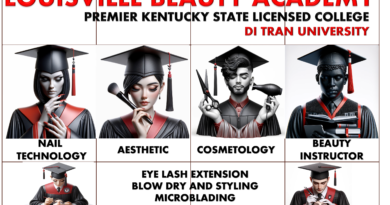

- Support educational institutions like Louisville Beauty Academy that focus on short, debt-free, employment-driven programs.

- Recognize short programs as critical workforce solutions with better job placement and economic impact than traditional cosmetology.

8. Elevating Louisville Beauty Academy (LBA)

- Louisville Beauty Academy is taking over the market and expanding rapidly because it adapts to technology, operates with a lean business model, and keeps an intense focus on student graduation.

- LBA accelerates training, teaches exactly what students need to pass licensing exams and succeed in the field, and offers post-graduation support at no additional cost.

- This student-centric approach, combined with efficiency and transparency, makes LBA a proven leader and a model for national reform.

Sources Referenced

- U.S. Department of Education GE Reports

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023–2025 data)

- Executive Order on Accreditation Reform (Apr 2025)

- New America Foundation Cosmetology Studies

- AACS v. DOE Court Briefs

- Historical OIG and BLS data on cosmetology licensee employment