NABA “Love Housing” Model: Integrated Affordable Housing, Health, and Wellness for Seniors

Introduction

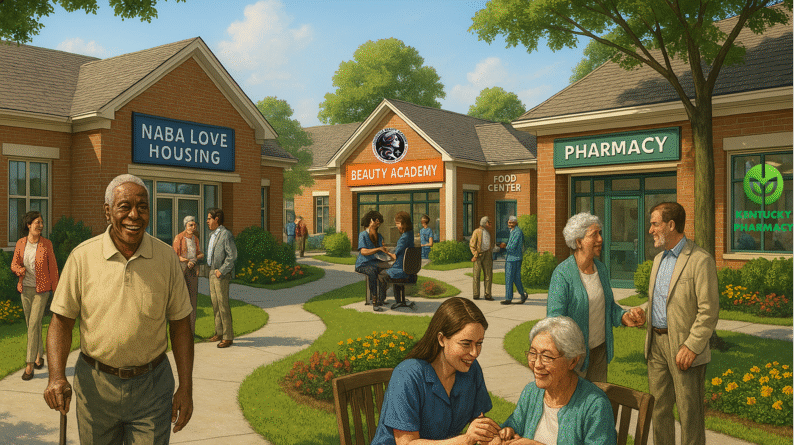

The NABA “Love Housing” model, envisioned by Louisville entrepreneur Di Tran, is a comprehensive ecosystem that combines affordable senior housing with robust on-site health and wellness services. It aims to serve both low-income seniors (via public subsidies) and self-funded elders who are attracted by the community’s wraparound support system. The model’s key components include:

- Lean-built affordable housing units (approximately $120,000 per unit) financed through federal HUD programs (e.g. Low-Income Housing Tax Credits), Section 8 vouchers, and private investment. These mixed-income communities house Section 8-eligible low-income seniors alongside moderate-income, self-paying seniors in a shared environment.

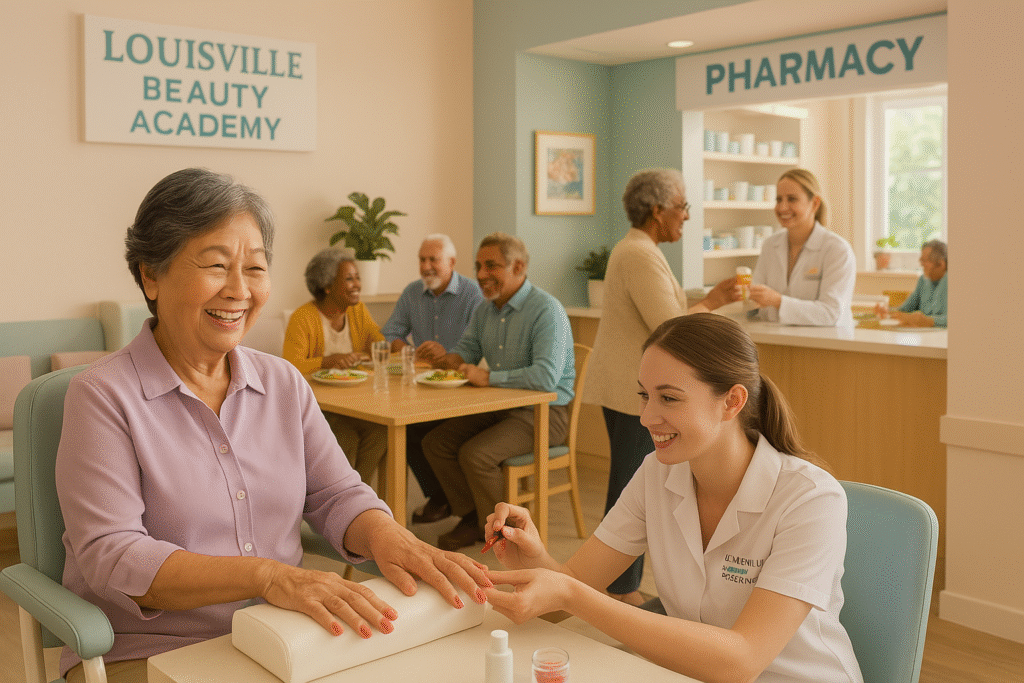

- On-site wellness and self-esteem services provided at no cost by students of a state-accredited beauty college (the Louisville Beauty Academy). Seniors receive regular grooming and beauty services – haircuts, styling, manicures, pedicures, facials – while enjoying daily social interaction with the student providers.

- On-site healthcare and monitoring, delivered through partners like Kentucky Pharmacy and other medical providers. Services include medication management, assistance with Medicare/Medicaid-covered care, and 24/7 technology-enabled monitoring (camera-based AI for safety, in-home sensors for health metrics like medication adherence or even blood/glucose levels, and facial/emotion recognition for early signs of distress).

- A purposeful community ethos that encourages social engagement and faith. Residents can opt into volunteer activities (e.g. helping pack food for charities, mentoring youth) and participate in group events – from faith-based gatherings to shared meals supported by programs like Dare to Care’s senior nutrition initiative.

This report analyzes the effectiveness and feasibility of the NABA Love Housing model. It will evaluate its cost-effectiveness, impact on health outcomes and psychological well-being (especially loneliness), scalability and replicability potential, and the return on investment (ROI) for both public stakeholders (e.g. government, healthcare systems) and private stakeholders (investors, partners). Comparisons are drawn to similar integrated senior living models and “health-housing” ecosystems to validate NABA’s approach with data and case studies.

Affordable Housing Built Lean: Cost-Effectiveness and Mixed-Income Feasibility

A foundational pillar of the model is providing high-quality affordable housing at a low per-unit cost (~$120k/unit). This is impressively lean considering that nationally the median development cost for new affordable apartments is around $204k per unit, with many projects far higher. Even in lower-cost regions like Texas, typical Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) units average $126k+, and in high-cost states they exceed $300k. Achieving $120k per unit suggests a highly cost-efficient construction and financing strategy, likely leveraging local cost advantages, streamlined design, and cross-subsidies (e.g. donated land or charitable contributions). Keeping construction costs low is crucial for cost-effectiveness: it means lower debt and operating costs, allowing rents to remain affordable to seniors on fixed incomes while still covering expenses.

Federal and state housing subsidies underpin the financial feasibility. The model would utilize LIHTCs (which attract private equity in exchange for tax credits) to cover a substantial portion of development costs. In addition, a segment of units would have Section 8 vouchers, meaning the government (HUD) pays the difference between what low-income tenants can afford and the fair rent. This ensures low-income seniors pay only ~30% of their income toward rent, while the property owner receives a stable subsidy income. Notably, only ~36% of eligible low-income older adults currently receive federal housing assistance (leaving millions with “worst case” housing needs). By providing more subsidized units, the model addresses an urgent gap in senior housing affordability.

Crucially, the NABA model is mixed-income: it welcomes self-funded seniors (who pay full rent) alongside subsidized residents. This mixture can enhance financial stability and social integration. Moderate-income elders – sometimes called the “middle-market” seniors – often earn too much to qualify for Medicaid or public housing but not enough to afford upscale senior living. The NABA community offers them a reasonably priced option with rich services, potentially filling a niche for the “forgotten middle” market. These self-paying residents improve the project’s revenue stream, while benefiting from the same supportive services environment. Mixed-income senior communities also avoid the stigma or segregation of “low-income only” projects, fostering a more diverse and vibrant community.

From a cost-effectiveness standpoint, integrating housing and care can yield significant public savings long-term. Stable housing itself contributes to better health by reducing homelessness or hazardous living situations among elders. Service-enriched affordable housing has been shown to support seniors’ independence and even reduce healthcare expenditures. For example, Vermont’s Support and Services at Home (SASH) program – which coordinates care in affordable senior housing – demonstrated slower growth in Medicare costs for participants and lowered Medicaid spending on nursing homes. Specifically, SASH participants had about $400 less in Medicaid long-term care expenses per person per year (by delaying nursing home placement) and significantly fewer emergency room and specialist visits. These savings illustrate how providing an appropriate housing+care environment can be cost-effective for public insurers. By keeping seniors healthier and out of institutions, the NABA housing model could similarly save government dollars.

Lean operations further enhance cost-effectiveness. The inclusion of the Louisville Beauty Academy’s student-provided services (discussed next) is essentially a low-cost or no-cost add-on – leveraging volunteer student labor as part of their training. Likewise, partnerships with healthcare providers may bring in services funded by Medicare/Medicaid (e.g. home health visits, pharmacy consults reimbursed by insurance), rather than needing all costs covered by the housing operator. Overall, the model creatively “braids” funding streams – housing subsidies, educational institutions, healthcare billing, charitable contributions – to minimize each individual stakeholder’s cost while maximizing value to the seniors.

“Beauty for Connection”: On-Site Wellness Services and Combatting Loneliness

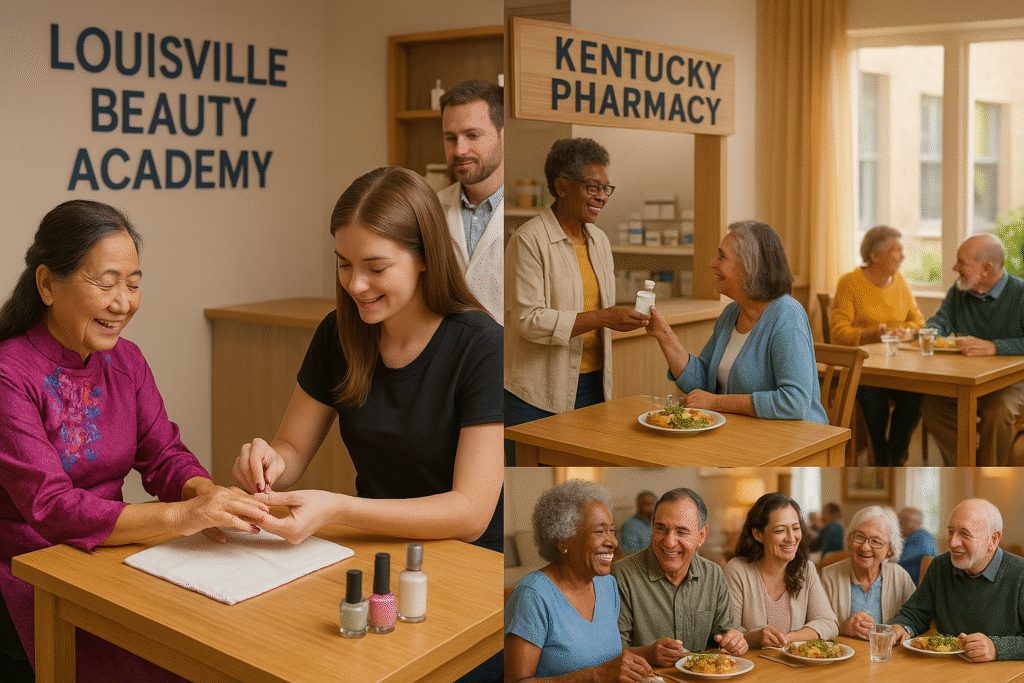

One of the most novel aspects of NABA’s model is the on-site wellness & self-esteem services delivered through a partnership with Louisville Beauty Academy (LBA). This state-accredited cosmetology school provides student trainees to serve the senior residents with regular grooming and pampering. While haircuts and manicures might sound like luxuries, they are in fact a powerful tool for improving seniors’ mental and social well-being. As the program’s mantra states, a simple haircut or nail trim is “not just a vanity service but a critical tool for human contact, dignity, and mental health” for isolated older adults.

LBA has piloted this concept in the community under an initiative called “Beauty for Connection.” Here’s how it works: as part of their required clinic hours, teams of beauty students regularly visit eldercare settings – nursing homes, senior centers, even homebound individuals – to provide free salon services. They engage clients with friendly conversation, gentle touch, and personal attention during these sessions. The impacts observed in the pilot have been striking. For the seniors, many of whom hadn’t had professional grooming in months due to mobility or cost barriers, the services produced immediate boosts in mood and self-worth. They “often brighten up considerably during and after the sessions,” and facility staff reported improved mood and engagement among residents on “spa day”. The human interaction – students listening to elders’ stories and treating them as individuals – directly combats loneliness and makes seniors feel cared for and less invisible.

These social benefits are not just anecdotal; they align with broader research on senior isolation. An estimated ~43% of seniors are socially isolated or lack regular meaningful contact. Chronic loneliness in older age is linked to serious health consequences, including a ~50% higher risk of developing dementia. Isolation also correlates with deteriorating physical health: without social and cognitive stimulation, cognitive decline can accelerate, immune function weakens, and mortality rates are higher. By infusing daily social interaction and caring touch into seniors’ lives, the “Beauty for Connection” approach is effectively a mental health intervention under the guise of beauty treatment. It provides something as important as medicine for many elders – companionship and a sense of dignity.

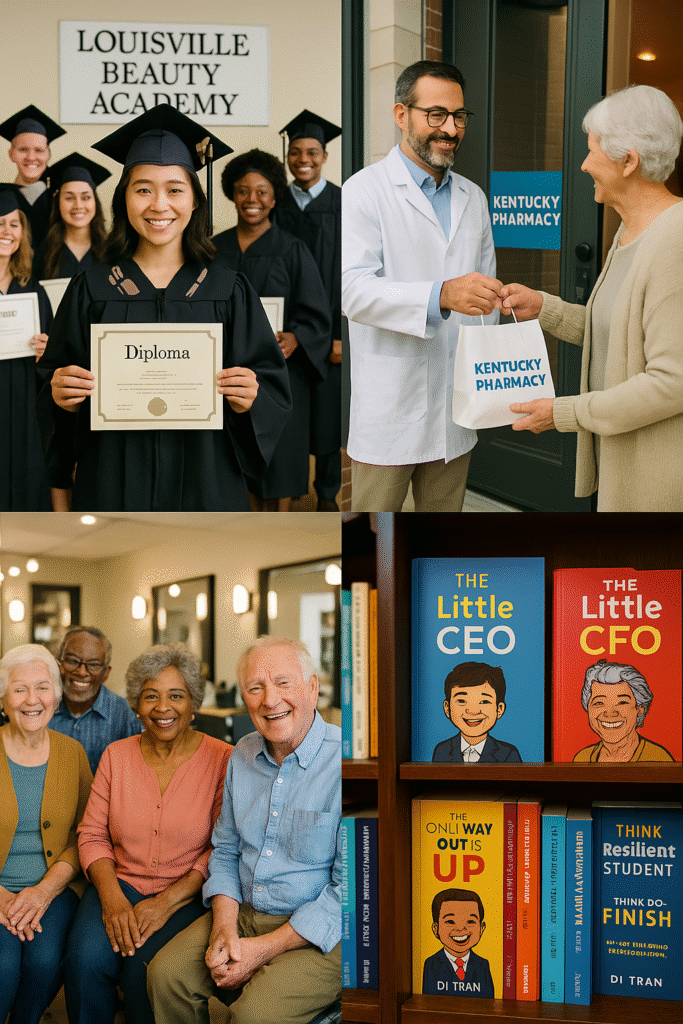

Equally important, this model is highly sustainable and scalable. The beauty students need real-life practice hours to complete their training, and typically cosmetology schools might have students work on mannequin heads or paying salon clients. LBA instead redirected a portion of those hours to community service for seniors. The students provide the labor free of charge, and the academy covers supervision and supplies through its normal budget and some donations. In essence, the educational mission subsidizes the community service mission. For the housing community, this means residents get regular wellness services at minimal additional cost. The only expenses are small (e.g. beauty supplies, transportation), which have been met through grants and donations. It’s a clever win-win: students gain experience and purpose, while seniors gain grooming care and friendship. LBA reports that students also benefit from this arrangement by practicing their technical skills on diverse clients (e.g. learning to cut hair for someone in a wheelchair) and by developing empathy and communication skills with older adults. The students find greater meaning in their work, knowing they are helping people in need – an added motivator that can enhance their training experience.

The health outcomes of such personal care visits can extend beyond smiles and haircuts. Proper grooming improves hygiene (which can reduce skin infections or foot problems for seniors who can’t easily bathe or trim nails themselves). Perhaps more significantly, alleviating loneliness and depression in the elderly can yield concrete medical savings. Stress and isolation contribute to higher blood pressure, heart disease, and depression in seniors. By reducing these risk factors, social interventions can potentially curb healthcare utilization. Louisville Beauty Academy estimates that by reducing loneliness and improving hygiene/mental health for underserved seniors, programs like “Beauty for Connection” could save $2–3 million in healthcare costs annually in Kentucky (by avoiding some falls, infections, or depressive episodes that would otherwise lead to expensive medical interventions). While that figure is an estimate, it underscores an important point: investing in social wellness yields dividends in health.

In summary, the NABA model’s free on-site beauty/wellness services are a low-cost, high-impact strategy to boost elders’ self-esteem and social connectedness. They directly address the epidemic of loneliness among seniors, which is increasingly recognized as a public health threat on par with smoking or obesity. By keeping residents groomed, engaged, and feeling loved, the model tackles the psychological outcomes that pure medical services often overlook. This holistic focus on mind, body, and spirit is a key differentiator of the “Love Housing” concept.

On-Site Healthcare and Smart Monitoring: Improving Health Outcomes

Beyond wellness services, the NABA model embeds actual healthcare resources on-site to address seniors’ medical needs proactively. A partnership with Kentucky Pharmacy suggests that an on-site or affiliated pharmacist is available to assist residents – for example, by reviewing medications, helping with refills, and coordinating with doctors. Medication management is a critical service for older adults: on average seniors in their late 60s take 5–8 medications daily, and the risk of adverse drug events is high if not managed carefully. In fact, about one in six hospital admissions of older adults is due to an adverse drug event (such as a dangerous medication side effect or interaction), a rate four times higher than in younger patients. By having pharmacists or healthcare professionals on-site, the community can conduct medication reviews, deprescribe unsafe drugs, and ensure residents take medications correctly. This likely prevents many errors and complications – e.g. avoiding duplicate prescriptions or contraindicated drugs – thereby reducing hospitalization risk. Studies in long-term care show that integrating pharmacists into senior care can significantly cut down on inappropriate medications and improve health outcomes. In short, ready access to a pharmacist/nurse helps keep residents safer and healthier.

The model also anticipates Medicare/Medicaid-supported clinical care on-site. This could take the form of visiting primary care providers, nurse practitioners, or therapists who hold clinic days in the building, or telehealth suites where residents can consult doctors virtually. Many seniors face mobility or transport barriers to seeing a doctor; bringing healthcare to them ensures preventive care and chronic disease management are not neglected. Early evidence from integrated care senior living models is very promising. For example, Juniper Communities (a senior housing provider) implemented an integrated care program (“Connect4Life”) with on-site care coordination and partnerships with health providers. The result was a 50% lower hospitalization rate for their residents compared to peers (0.30 hospitalizations per person-year vs. 0.65 in a comparable population). This dramatic reduction in hospital visits translated to saving $3.9–$6.0 million in Medicare costs each year for a group of just 471 seniors. Extrapolated broadly, such a model could save billions in healthcare spending. The lesson is clear: when seniors receive coordinated, on-site healthcare attention, many acute crises (ER visits, hospital stays) can be avoided through timely intervention. NABA’s plan to integrate medical services thus not only benefits resident health but could yield substantial ROI for healthcare payers (Medicare, Medicaid) in avoided costs.

A particularly innovative element is the use of 24/7 monitoring technology, including camera-based AI observation and in-home sensors. With residents’ consent, unobtrusive cameras or sensors in apartments can watch for signs of trouble – for instance, detecting if someone has fallen or if their daily activity pattern changes in a concerning way. Advanced “ambient” sensors (motion detectors, smart floor mats, bed sensors) and AI algorithms can alert staff to emergencies in real time (e.g. a fall in the bathroom) or subtle changes (walking speed slowing, missed meals) that might indicate emerging health issues. Research on AI-assisted remote patient monitoring in elder care shows it can significantly improve safety and outcomes. Vision-based AI fall detection allows caregivers to monitor many residents at once and respond immediately when a fall or abnormal event is detected. Some estimates suggest that AI fall prevention systems can reduce future fall risk by 60% and cut emergency room visits by up to 80% by enabling earlier interventions. That is a staggering impact, given falls are one of the leading causes of injury and hospitalization in seniors. In addition, continuous data from wearables or environmental sensors can create baselines for each resident’s normal routines. AI can then flag deviations – for example, if a normally active resident stays in bed all day, or if someone’s night-time bathroom visits increase (potential sign of a urinary infection or medication issue). By catching problems early, staff can arrange a doctor visit or adjust care before the issue escalates into an ER trip. This proactive monitoring epitomizes the model’s philosophy of preventive, not just reactive, care.

Another cutting-edge aspect is facial and emotional expression detection AI. This technology analyzes residents’ facial micro-expressions, tone of voice, and behavior to infer emotional states. It essentially gives caregivers a “sixth sense” to identify if a senior is anxious, depressed, or in pain – even if they don’t or can’t verbally communicate it. This is particularly valuable for those with cognitive impairments like dementia, who may not articulate distress. An emotion AI system can, for example, detect increasing signs of withdrawal or apathy in a resident, which might indicate the onset of depression or acute loneliness. It serves as an early warning system for emotional isolation, prompting staff to intervene with more social support or counseling before the issue worsens. In a senior community where many may be far from family, such real-time emotional monitoring ensures no one’s silent suffering goes unnoticed. Rather than replacing human empathy, this AI augments it – giving staff data-driven insights so they can direct attention to residents who need a morale boost or mental health check-in. Ultimately, by addressing seniors’ emotional well-being (and not just physical health), the model provides truly comprehensive care. This can improve quality of life and also has health payoffs, since depression and social isolation are risk factors for a host of medical issues.

In summary, the NABA housing model’s health and tech integration is poised to yield significant health outcome improvements. Ready access to healthcare services will likely lead to better management of chronic conditions (avoiding complications) and fewer catastrophic events (like undetected strokes or medication errors). The combination of human care (pharmacists, nurses) and high-tech care (AI monitors, telehealth) creates a safety net around each resident’s well-being. Evidence from similar “health + housing” initiatives (Juniper’s Connect4Life, Vermont’s SASH, etc.) validates that this approach can reduce hospitalizations, control costs, and keep seniors living more independently. For the seniors, this means longer, healthier lives in their own home rather than in a hospital or nursing facility. For the public and healthcare system, it means a more efficient allocation of resources, focusing on prevention and early detection rather than paying for expensive acute care after a crisis has occurred.

Community and Purpose: Reducing Isolation Through Engagement

Another core goal of the “Love Housing” model is to foster a thriving community where seniors have purpose and connection. Loneliness and isolation are addressed not only through the wellness and monitoring services above, but also through structured opportunities for engagement. The model encourages residents (as they are willing and able) to participate in activities like volunteering and mentorship, group gatherings, and faith-based practice. These may seem like “extras,” but they are in fact critical to the model’s psychological and social impact.

Providing avenues for seniors to volunteer or serve others is a powerful antidote to the passivity and loss of purpose that many older adults experience. For example, residents might help pack food boxes for those in need (partnering with a local charity or food bank), or tutor and mentor neighborhood youth (perhaps through a “grandparents mentoring” program). Research consistently shows that seniors who engage in volunteering reap substantial health benefits. A large study in older adults found that dedicating about 2 hours per week to volunteering was associated with lower depression, better physical health, and even reduced mortality rates compared to non-volunteers. Volunteering gives elders a sense of purpose and accomplishment, which translates into higher life satisfaction and self-esteem. It also keeps them physically and mentally active – which can help maintain mobility and cognitive function. In fact, older volunteers have been found to have lower rates of hypertension and delayed physical disability, likely because staying active and socially engaged buffers against stress and frailty. Importantly, volunteering also expands seniors’ social networks, protecting against isolation. Through service, residents form friendships and enjoy the camaraderie of working toward a common cause.

The model’s inclusion of faith-based activities (for those interested) likewise builds community and personal meaning. Many seniors derive strength and social ties from faith communities. Group prayer, devotional meetings, or religious services on-site can be a source of comfort and a way to bond with neighbors over shared values. This can be especially important for elders who can’t easily travel to their former places of worship – the community brings that experience to them. Studies have indicated that religious engagement in seniors correlates with better mental health and coping, and faith communities often act as an additional support network.

Additionally, partnerships with meal support programs like Dare to Care ensure no resident goes hungry and that communal meals can be enjoyed. Dare to Care’s senior outreach, for instance, provides monthly packages of nutritious food to low-income seniors with the explicit goal of improving their health through better nutrition. By tapping into such programs, the housing model not only fights food insecurity (a common issue among low-income elders who may skimp on groceries to afford rent or medicine) but also creates occasions for social dining. Shared meals – whether a subsidized lunch program in a common room or group potlucks – help knit the community together. Breaking bread with others reduces loneliness and gives residents something to look forward to each day.

All these community features work in synergy to dramatically reduce loneliness and isolation among residents. The positive effects are backed by data: in one survey, 61% of older adults said their feelings of loneliness improved after moving into a senior living community, largely due to increased opportunities for social interaction. Likewise, a UK study found that seniors in “housing with care” communities (which combine housing and support services) reported significantly less loneliness than a comparable group living alone, thanks to the built-in social environment. NABA’s model, with its rich array of engagement options, is poised to create just such an environment. Residents can choose to be as active as they like – whether that’s attending a weekly game night, gardening in a community plot, packing meals for the hungry, or leading a prayer group. The key is choice and inclusion: no one is forced, but everyone is invited, regardless of physical limitations (activities can be adapted so even those with disabilities can contribute in some way).

By giving seniors roles as volunteers, mentors, neighbors, and friends, the model combats the deleterious “retirement home blues” where people feel they’re just waiting passively. Instead, residents maintain a sense of identity and usefulness. This has tangible health benefits: volunteers in Senior Corps programs reported decreases in anxiety and depression and improved overall health after a year of service. Another study noted 84% of older volunteers reported stable or improved health after two years in a service program, in contrast to typical declines with aging. Clearly, engagement is therapeutic. In a very real sense, the NABA Love Housing community functions not just as a residence, but as a supportive family where each member is valued and needed. This climate of love, purpose, and mutual support is at the heart of what makes the “Love Housing” model effective beyond just bricks and mortar.

Scalability and Replicability of the Model

A critical question is whether this integrated model can be scaled and replicated beyond a single showcase community. The concept is ambitious, as it weaves together housing, education, healthcare, and social services. However, each component of the model has precedents or analogues elsewhere, suggesting it can indeed be reproduced in other locales with the right partnerships and commitment.

Housing and funding scalability: The financing approach (LIHTC credits, vouchers, blended income tenants) is a standard template in affordable housing development. Thousands of LIHTC senior housing properties exist across the U.S. – what NABA proposes is to build in an even more cost-effective way (hitting that $120k/unit mark) and layer on services. If the pilot demonstrates success, it could attract more investors (including impact investors or social bonds) by proving that such communities can be financially viable and achieve desirable outcomes. The mixed-income approach means the model isn’t entirely dependent on subsidies; a portion of market-rate units can improve the balance sheet, making it attractive to private developers as well. The key will be showing that offering the extra services (beauty, healthcare, etc.) does not make operating costs prohibitive. Given that many of those services are funded by external streams (education budgets, Medicare billing, volunteers), the additional cost to the housing operator is relatively modest. Thus, from a pure real estate perspective, the model could be replicated by other mission-driven developers or nonprofits that partner with local service providers in their area.

Beauty Academy/Wellness replication: The concept of a beauty school providing free services to seniors could be expanded to any city that has a cosmetology program. There are hundreds of cosmetology schools nationally; many could adopt a similar “community service” module in their curriculum. In fact, Louisville’s “Beauty for Connection” program is itself based on community-based beauty education that could be promoted as a best practice. Even absent a beauty school, communities could partner with volunteer beauticians or nonprofits (e.g. programs like “Haircuts for Seniors” or mobile salon charities). The low cost and high impact of this intervention makes it a replicable piece. It might require advocacy to cosmetology boards or school accrediting bodies to allow off-site service hours, but LBA has demonstrated it’s feasible within regulatory standards. Scaling this nationally could create a whole army of beauty students combating senior loneliness one haircut at a time.

Healthcare integration scalability: In recent years there’s a noticeable trend of convergence between senior housing and healthcare, which bodes well for replicating NABA’s health integration. Large senior living providers are forming partnerships with healthcare entities (hospitals, Medicare Advantage insurers, telehealth companies) to bring services on-site. The regulatory environment is also shifting to support this – for example, Medicare Advantage plans can now cover certain non-medical services and wellness benefits in housing communities. This means an operator of a senior community can potentially get reimbursed for providing care coordination or using health devices, especially if they partner with a health plan. The NABA model could tap into these opportunities, and other communities can follow suit. Technologies for remote monitoring (like sensor networks or AI cameras) are increasingly available as turn-key solutions from healthtech companies, making them easier to implement at scale. As an example, companies like Sentrics offer integrated platforms (with fall detection, engagement tools, data analytics) specifically designed for senior living providers. This suggests that as long as a community has decent internet infrastructure, they can adopt similar monitoring systems – it’s not science fiction, but off-the-shelf technology now. Of course, staffing is needed to respond to alerts, but the improved efficiency (one staff can remotely watch over dozens of residents) helps manage labor needs. In replication, some smaller communities might opt for a scaled-down version (e.g. a wearable pendant or periodic telehealth checks if 24/7 AI cameras are too costly), but the principle of tech-aided oversight is widely applicable.

A noteworthy aspect is that integration requires collaboration. To replicate NABA’s model in another city, you’d need a coalition: a housing developer, a local beauty school or volunteer network, a willing healthcare provider (pharmacy, clinic, or health system), and possibly backing from nonprofits or churches for the community activities. This is complex, but not insurmountable. The model can be seen as a template or toolkit that local stakeholders can adapt. For instance, in another state the partners might be different (instead of Louisville Beauty Academy, maybe a community college cosmetology program; instead of Kentucky Pharmacy, maybe a visiting nurse association and a mobile pharmacy service). The unifying idea is to co-locate and coordinate services around housing. Many communities are already exploring similar “hub” concepts for aging-in-place. The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), while not housing-based, shows that a one-stop-shop for senior care is highly effective – PACE keeps frail seniors living in their homes by providing transportation to a day center for all medical, therapy, and social needs, drastically reducing nursing home admissions. NABA’s model is essentially creating a PACE-like hub within a housing complex, which could be even more convenient.

Policy support can further enhance scalability. If government funders see positive outcomes (health improvements, cost savings), they might provide grants or incentives to expand this model. For example, state housing finance agencies could create bonus LIHTC allocations for projects that include health/wellness partnerships. Or healthcare innovation grants could help cover the cost of implementing monitoring technology in affordable housing. With the demographic wave of aging baby boomers, the pressure to find scalable solutions for senior housing and care is enormous. Thus, the timing is ripe for models like NABA’s to attract attention and resources.

Potential challenges: One must acknowledge scaling isn’t without challenges. Coordination among multiple sectors (housing, healthcare, education) can be difficult – it requires alignment of goals and funding streams. There could be regulatory hurdles (e.g. privacy concerns with cameras in units, licensing issues for providing medical care in a residential setting, etc.) that need ironing out. Workforce is another consideration: expansion means training more students or volunteers to deliver those personal services, and ensuring healthcare staff are available for on-site care (perhaps through creative staffing or telehealth). However, none of these challenges are deal-breakers; they are manageable with community buy-in and smart policy adjustments. In fact, the success of programs like SASH in an entire state (Vermont) indicates that service-enriched senior housing can be implemented at scale (SASH now serves thousands of seniors via a network of housing sites, coordinating with local agencies). This gives confidence that the NABA model, once proven, could be rolled out in multiple communities, adapting to local needs while adhering to the same core philosophy.

Return on Investment (Public and Private)

The integrated model aims to generate a “win-win” ROI for both public stakeholders (like government health programs) and private participants (developers, investors, service providers). We will consider each in turn:

- Public/Government ROI: The biggest savings for the public sector come from healthcare cost reductions. By keeping seniors healthier, more independent, and out of high-cost institutions (hospitals, nursing homes), the model can save Medicare and Medicaid significant money. We’ve already cited examples: Vermont’s service-enriched housing program slowed Medicare expenditure growth and cut Medicaid nursing home costs (~$400 less per person/year); Juniper’s integrated care model in private senior living halved hospitalizations, projecting over $10 billion in potential Medicare savings if widely adopted. Additionally, Louisville Beauty Academy’s initiative projected $2–3 million in healthcare savings in one state from improved senior wellness. These figures highlight that even moderate improvements in seniors’ health and reduction in emergency events translate to millions saved. For Medicaid (which funds long-term care for low-income seniors), delaying or preventing just a few nursing home placements yields enormous savings – a nursing home can cost $90–$100k per year per person, whereas supporting that person in an affordable housing community with some services might cost a fraction of that. If a model like NABA’s can keep, say, 50 seniors out of nursing homes for a year by keeping them stable at home, that could easily save $4–5 million in Medicaid spending just for those individuals. Moreover, healthier seniors are less likely to call 911, less likely to need expensive specialist care, and may have shorter hospital stays when they do go (because issues are caught earlier). All of these contribute to a positive ROI for public health systems. There’s also a social ROI: seniors who are healthier and happier place less demand on social services like emergency food aid or crisis interventions. In essence, investing in this model upfront (through housing subsidies or support for the on-site services) can avert larger downstream costs, a classic case of “pay now to save later.”

- Private/Investor ROI: For private investors and developers, the ROI in a traditional sense (financial profit) for affordable housing is often modest but steady – LIHTC deals usually yield returns via tax credits and stable rents. The NABA model, by incorporating mixed-income tenants and potentially partnering with healthcare payers, could open new revenue streams. For instance, a senior community that achieves demonstrable health outcomes might partner with a Medicare Advantage insurer to receive stipends or shared savings payments (some senior living operators are exploring value-based payment models where they get bonuses for reducing hospitalizations among their residents). The Sentrics report quoted a CEO noting that if a senior living facility invests in care coordination and tech, managed care plans will want to send people there because it lowers costs. This implies potential referral partnerships and higher occupancy driven by healthcare networks. Higher occupancy and reputation for quality can improve an investor’s returns. Additionally, the inclusion of self-pay units means the property isn’t limited to below-market rents for all units – those moderate-income residents pay closer to market rate, which can improve cash flow. Another aspect is length of stay: an integrated community can keep residents living there longer (because their health needs are met even as they age). Longer average tenancy means less turnover cost and more rent collected over time per resident. Connect4Life, for example, noted increased resident length of stay as a benefit of their model. For an investor, a longer length of stay and lower vacancy is absolutely a financial gain.

There is also intangible ROI for private stakeholders: the partners like the beauty academy or pharmacy gain community goodwill, publicity, and fulfillment of their missions. The beauty academy by participating demonstrates its social responsibility and possibly attracts students who are excited about its community role. The pharmacy or healthcare provider might gain a loyal customer base (residents who will use their services) and the opportunity to expand into a new service-delivery model (which could become profitable if they manage capitated payments or billing for on-site services). In other words, private partners can leverage the model to differentiate themselves in the market. In senior housing, for example, offering a unique integrated wellness environment could be a selling point to attract the growing cohort of middle-income seniors looking for value. This competitive edge can translate to better market share – an ROI in itself.

Societal ROI is also worth noting. While harder to quantify in dollars, the model produces considerable social value: improved quality of life for elders, reduced caregiver burden on families (knowing their loved one is in a supportive environment), and community volunteer opportunities. Programs like this can strengthen intergenerational bonds (through youth mentorship) and create more age-friendly communities, which has ripple benefits. Public and philanthropic investors often consider these social returns (measured in things like reduced loneliness rates, increased life satisfaction, etc.) as equally important as financial returns.

Overall, when measuring ROI comprehensively, the NABA Love Housing model appears to deliver high value for cost. It tackles multiple costly problems (housing insecurity, healthcare utilization, loneliness) in one integrated solution. A traditional analysis might look at cost per resident versus savings: if, for example, providing the wraparound services costs an extra $300 per month per resident (just a hypothetical number for staffing/tech etc.), but reduces healthcare spending by $500 per month per resident, the net societal benefit is $200 per person per month – and seniors are happier to boot. Such calculations will ultimately need real data from pilot implementations, but the analogous programs cited suggest the balance will be favorable. As one Harvard analysis succinctly put it, “service-enriched affordable housing has been shown to support independence — and reduce healthcare costs”. That dual outcome – elders living with dignity at lower public cost – is the ultimate ROI that both government and private society can get behind.

Comparison to Similar Models

The NABA Love Housing model is part of a broader movement recognizing that housing, healthcare, and social well-being for seniors must be addressed together. While its combination of elements is unique (particularly the beauty academy component), there are comparable models and case studies that validate many of its principles:

- Supportive Housing with Services (e.g. SASH in Vermont): As discussed, SASH links affordable senior housing sites with care coordinators and wellness nurses who arrange services for residents. Like NABA’s model, SASH is cost-effective and improves health outcomes, yielding slower Medicare spending growth and reduced Medicaid long-term care costs. SASH participants have better control of chronic conditions (for example, average blood pressure readings improved significantly among participants due to on-site wellness programs) and report feeling more secure with the support. SASH has been highlighted as a national “success story” in integrating housing and health, demonstrating that even in a largely rural state, a networked approach to service-enriched housing can thrive. NABA’s model is akin to a single-site, deeper version of SASH – with actual services delivered on premises (beauty, pharmacy) – whereas SASH often coordinates external services. The positive SASH results bolster the case that NABA’s more intensive model will see success.

- PACE and All-Inclusive Care Programs: The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is a Medicare program that provides comprehensive medical and social services to frail seniors, enabling them to live at home instead of nursing homes. PACE achieves outcomes like fewer hospitalizations and high patient satisfaction through an interdisciplinary care team, adult day health center, and home support. NABA’s model can be seen as complementary – if a PACE program were to partner with an affordable senior housing community, the effect would be very similar to what NABA envisions (housing + all needed services). Some communities have indeed started co-locating PACE centers within senior housing complexes. The success of PACE (which often reports better health outcomes and comparable or lower costs than nursing homes) indicates that bundling services in one setting improves senior care efficiency.

- Assisted Living and CCRCs (Continuing Care Retirement Communities): Higher-income seniors often live in CCRCs or assisted living facilities that provide housing with meals, personal care, activities, and some health services. The NABA model is essentially bringing many benefits of assisted living (social activities, help with meds, on-site health monitoring) into an affordable context. Studies of assisted living show that residents experience improvements in loneliness and nutrition when they move from isolated homes into a community that provides daily interaction and support. However, traditional assisted living is private-pay and costly. NABA’s approach could be viewed as a “Affordable Assisted Living” model – it strives to offer a comparable support environment financed through public means for those who can’t afford private fees. There are some precedents, such as Medicaid waiver programs in certain states that fund services in assisted living for low-income seniors. Those have shown reduced nursing home entries and good resident outcomes. NABA’s model goes a step further by embedding unusual services (beauty school, cutting-edge AI) not typically found even in expensive facilities. This positions it ahead of the curve, but comparable enough to demonstrate feasibility (since assisted living communities do prove that seniors value having on-site services and are healthier/happier with them).

- Intergenerational and Volunteer-Based Housing: Another related concept is housing that intentionally mixes seniors with younger populations or volunteer opportunities. For example, the Hope Meadows community in Illinois placed seniors and foster/adoptive families together – seniors received free or low-cost housing in exchange for volunteering time with youth. The results were heartwarming: the elders gained a new sense of family and purpose, and the children benefited from extra love and attention. Similarly, some universities have programs where college students live for free in senior homes to provide companionship, which reduces seniors’ loneliness markedly. The NABA model’s mentorship and volunteer facets echo these examples, affirming that engaging seniors in altruistic or intergenerational roles yields mutual benefits. Case studies show seniors in those programs experience improved mental health and a rekindled sense of purpose in life, which NABA aims to replicate with its service opportunities.

- Tech-Enabled Aging-in-Place Initiatives: Around the world, various pilots have used smart home technology to help seniors age in place safely. In Japan and parts of Europe, for instance, sensors in senior apartments (even toilets that analyze urine, motion sensors for daily habits) have been trialed to detect health changes early. These pilots often demonstrate fewer emergencies and quicker medical responses when tech is in place. One U.S. example is the CAPABLE program (Johns Hopkins School of Nursing) which, while primarily a home modification and nursing intervention program, also employs simple technology and saw significant reductions in disability and depressive symptoms among low-income seniors, ultimately saving Medicare costs by reducing hospitalizations. NABA’s heavy use of AI and sensors puts it at the forefront of this trend. While not many affordable housing communities have such advanced systems yet, the direction of research suggests that tech-enabled care will become more common due to its effectiveness. The McKnight’s article we cited earlier notes that staff in nursing homes appreciated AI remote monitoring because it eased their workload and assured them they wouldn’t miss urgent issues. This acceptance is growing, meaning replication will get easier as the industry embraces these tools.

In comparing these models, what stands out is that NABA’s “Love Housing” is a holistic fusion: it takes the service coordination of SASH, the comprehensive care ethos of PACE, the social environment of assisted living, the volunteerism of Hope Meadows, and the tech innovation of aging-in-place pilots – and blends them into one community model. Few, if any, existing communities have all these elements under one roof, especially in an affordable housing context. This integrated approach is cutting-edge, but not unproven, because each individual element has a track record in some form. The model’s effectiveness is bolstered by evidence from these analogous efforts. Seniors in environments with rich social programming and available healthcare do better than those without. The combination simply amplifies the benefits.

Conclusion

The NABA Love Housing model represents an innovative, compassionate approach to senior living that aligns housing, healthcare, and human connection. Our deep-dive analysis finds that the model is not only visionary but grounded in practical evidence:

- It addresses urgent needs (affordable housing for a growing low-income senior population, who often otherwise face untenable housing cost burdens). By leveraging tax credits and vouchers, it can deliver quality housing at low cost, which is economically prudent and socially just.

- It smartly leverages existing resources (student beauticians, healthcare reimbursements, technology) to provide services that greatly enhance seniors’ quality of life with relatively little incremental cost. This makes it cost-effective and likely sustainable long-term.

- It promises better health outcomes: reduced loneliness and depression through social engagement, better chronic disease management and fall prevention through on-site care and monitoring, and potentially lower rates of serious health events. The downstream effect is fewer ER visits, hospital stays, and nursing home placements – benefits demonstrated in similar integrated care models.

- It fosters a true community of purpose, giving elders roles as volunteers, mentors, neighbors and thereby combating the isolation that plagues so many older adults. The psychological boost from this is immense – translating into measurable health improvements (lower stress, higher life satisfaction, even longevity gains).

- It shows signs of being scalable and replicable. While requiring cross-sector collaboration, it aligns with trends in both housing policy and healthcare innovation. With supportive policy and partnerships, it could be reproduced to serve seniors in many other communities, bridging the gap between siloed housing and healthcare systems.

For public stakeholders, the model offers a path to optimize use of funds: instead of paying for costly institutional care or emergency interventions, investing in integrated communities can yield healthier seniors and significant savings (as evidenced by case studies of reduced Medicare/Medicaid expenditures). For private stakeholders, it demonstrates a socially responsible model that can still be financially viable – with steady occupancy, potential healthcare partnerships, and an enhanced reputation driving value.

In essence, the NABA Love Housing model validates the concept that “housing is healthcare” – and expands it further to “housing is healthcare and family.” By wrapping affordable homes in a blanket of love, care, and connection, it tackles the full spectrum of needs that aging citizens have. The data and examples reviewed strongly support that such a model can improve seniors’ health, happiness, and longevity while being economically sensible for society. If Di Tran’s vision comes to fruition, it could serve as a national exemplar of how to help seniors age optimally: not in isolated silos or unaffordable facilities, but in a community that truly feels like home – with open doors, helping hands, and hearts full of hope.

Sources

- Tran, Di. Affordable Housing and Wellness: Supporting Optimal Aging in Kentucky’s Underserved Seniors. New American Business Association Inc., April 11, 2025. (Analysis of housing insecurity among Kentucky seniors and integrated housing-health solutions)

- Louisville Beauty Academy. “Beauty for Connection”: A Proven Model to Combat Loneliness and Deliver Free Wellness Services to Kentucky’s Elderly. (Description of LBA’s student-led beauty services program and its outcomes in reducing senior loneliness and improving health)

- Pretorius, R.W. et al. “Reducing the Risk of Adverse Drug Events in Older Adults.” American Family Physician, vol. 87, no.5, 2013, pp. 331-336. (Statistics on medication-related hospital admissions in seniors; one in six admissions due to adverse drug events)

- McKnight’s Long-Term Care News. “The value of AI for monitoring seniors’ health.” Oct. 2022. (Overview of AI-enhanced remote monitoring; estimate that AI can reduce falls by 60% and ER visits by 80%)

- Philipson, Bent. “How Emotion AI Can Help Us Personalize Senior Care.” Oct. 2023. (Explains emotion-detecting AI in elder care and how it identifies isolation or distress from facial and vocal cues, enabling early intervention)

- Mayo Clinic Health System. “Helping people, changing lives: 3 health benefits of volunteering.” Aug. 1, 2023. (Discusses research on older adult volunteering; linked to better mental and physical health, lower depression, and increased life satisfaction in seniors)

- Dare to Care Food Bank – Senior Programs. “Senior Outreach | Dare to Care.” (Details the federal Commodities Supplemental Food Program providing monthly food boxes to low-income seniors to improve their health)

- Molinsky, Jennifer. “Housing for America’s Older Adults: Four Problems We Must Address.” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, Aug. 18, 2022. (Highlights need for affordable, accessible senior housing and notes that service-enriched housing supports independence and reduces healthcare costs)

- SASH (Support and Services at Home) Vermont – Our Results. (Summarizes outcomes of the SASH program: improved blood pressure control, slower growth of Medicare costs, and $400/year Medicaid savings per person by delaying nursing home care)

- Sentrics. “The Convergence of Healthcare and Senior Living Communities.” (Cites Juniper Communities’ data on integrated care model Connect4Life: 0.30 hospitalizations per person-year vs 0.65 average, saving Medicare ~$4–6 million annually for ~471 seniors; indicates potential $10B+ savings if scaled)

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data and Oversight…” GAO-18-637, 2018. (Found median LIHTC development cost $204k/unit in 2011–2015; median $218k for new construction, ranging from ~$126k in low-cost states to $326k in high-cost states).

🧮 Total Estimated Project Cost for 40-Unit NABA Love Housing Model with Community Services – FOLLOWS DI TRAN ENTERPRISE SINGLE-BEDROOM INDEPENDENT UNIT ABOVE

Based on current U.S. construction costs for compact independent homes:

🏠 Residential Units (40 total)

- Average cost per unit: $100,000

- Total residential cost: $4,000,000

🏢 Community Service Units (10 total)

Includes facilities for:

- Louisville Beauty Academy student salon

- Kentucky Pharmacy healthcare space

- Optional dental care suite

- Shared wellness and gathering space

- Estimated size: ~2.5× the square footage of a regular unit

- Average cost per service unit: $250,000

- Total service unit cost: $2,500,000

💰 Total Project Estimate: $6,500,000

This cost covers:

- 40 ADA-accessible residential units

- 10 multi-use service units supporting community wellness

- Energy-efficient construction, modular design potential

- Long-term low maintenance and operating costs

- Built-in service ecosystem that promotes elder independence and dignity

📌 This estimate does not include land acquisition, utility infrastructure, or advanced technology layers (e.g., AI monitoring), which may require additional budgeting.