Louisville Beauty Academy’s Model vs. Typical U.S. Beauty Schools: A Comprehensive Comparison

Introduction

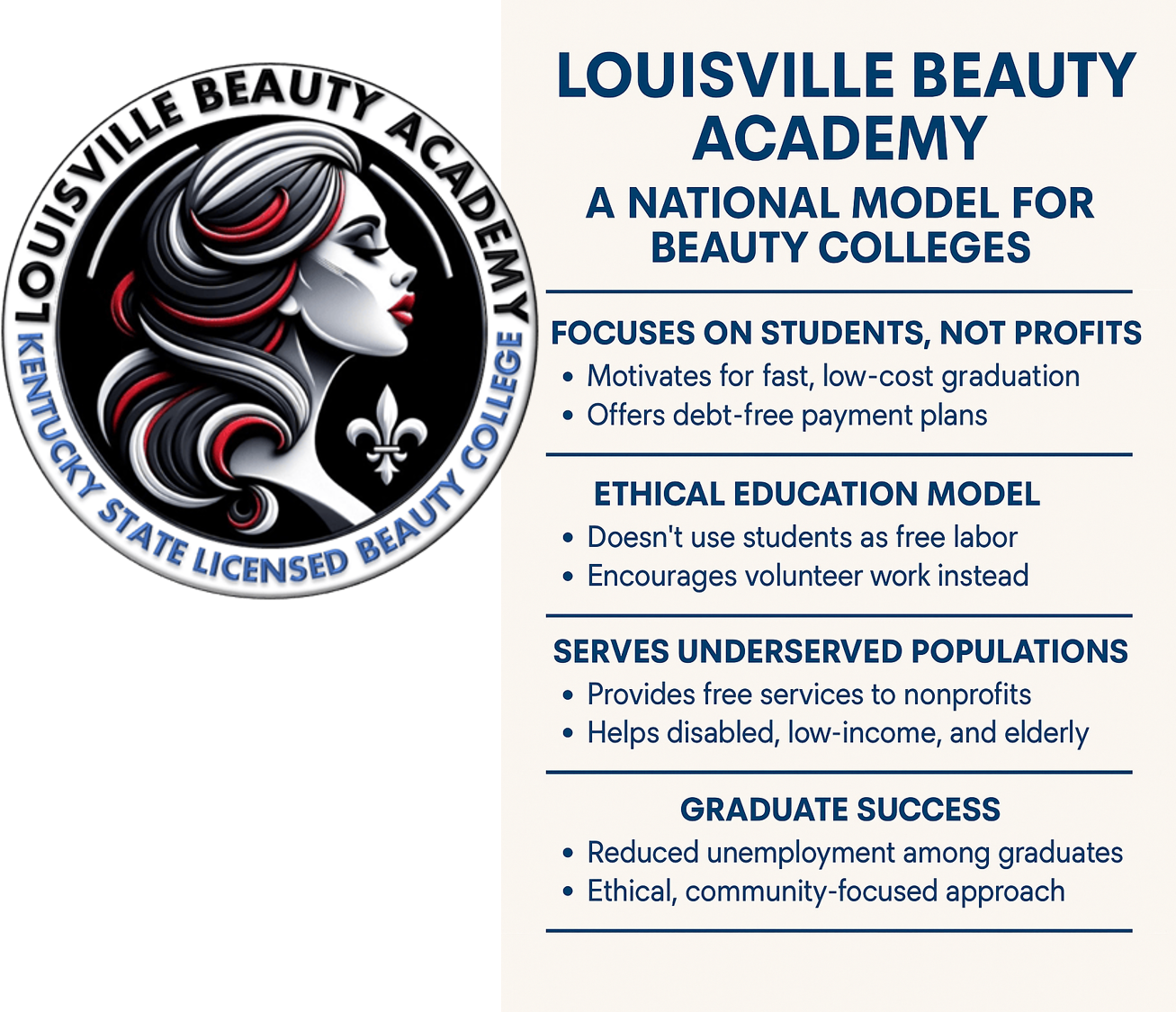

Louisville Beauty Academy (LBA), led by CEO Di Tran, has drawn attention for its unconventional approach to beauty education. Unlike many for-profit cosmetology schools that have been criticized for lengthy programs, high debt, and exploitative practices, LBA claims to offer fast-track, affordable training rooted in ethical standards and community service. This report investigates whether LBA is truly unique in the U.S. beauty school landscape for:

- Accelerated graduation programs that help students finish quickly,

- Low-cost, debt-free payment models that avoid exploiting federal financial aid,

- Ethical training practices that prohibit using students as unpaid salon labor,

- Structured volunteerism serving underserved groups (disabled, low-income, elderly), and

- High graduation rates and job placement success for its students.

We compare LBA’s model to common practices among other U.S. beauty schools, which often include prolonged programs (maximizing Title IV financial aid), use of student labor in school-run salons, and graduates left with generalized training, debt, and poor employment outcomes. The analysis incorporates program length, cost structures, student labor policies, community service initiatives, and outcome data, supported by citations from verifiable sources.

Louisville Beauty Academy’s Unique Approach

Accelerated, Focused Programs for Rapid Graduation

LBA emphasizes efficient training paths that match students’ specific career goals, enabling faster completion than traditional one-size-fits-all cosmetology programs. Each licensure program is offered as a standalone track with only the state-required hours: for example, Nail Technology (450 hours), Esthetics (750 hours), Shampoo Styling (300 hours), and Cosmetology (1,500 hours). By allowing students to pursue a narrower specialization if they wish, LBA spares them from unnecessary extra coursework. A student who only wants to be a nail technician can finish after 450 hours instead of being funneled into a full 1,500-hour cosmetology course. This targeted approach saves time and accelerates entry into the workforce. In fact, the fastest a full cosmetology program can typically be completed is around nine months (for ~1500 hours), and LBA’s flexible scheduling (open-enrollment and self-paced attendance) allows motivated students to meet such timelines. By contrast, many beauty schools pressure all students into the longest program (cosmetology) even if they only intend to practice in one area, a practice driven by profit incentives rather than student need (discussed further in a later section).

Low-Cost, Debt-Free Education Model

LBA is distinguished by its affordability and “no-debt” philosophy. Under Di Tran’s leadership, LBA offers substantial scholarships covering 50% to 75% of tuition for many students. This dramatically lowers out-of-pocket costs – for example, the 450-hour Nail Technology program’s tuition can be as low as \$3,800 with scholarships, compared to over \$20,000 for a typical 1,500-hour cosmetology program at other schools. Even the comprehensive cosmetology program at LBA (standard tuition around \$24,000 for 1500 hours) is often half-price or less after scholarships and discounts. Crucially, LBA discourages student loans entirely. The school provides zero-interest payment plans and structures tuition so that students can pay as they progress without needing federal financial aid. This debt-free approach means graduates aren’t saddled with large loan balances. “No-debt mindset” is a core policy at LBA, aiming to protect students (many of whom are low-income or immigrants) from the long-term burden of loan repayment. In sum, LBA’s cost structure is student-centered, prioritizing access and financial freedom over maximizing revenue.

By contrast, most beauty schools rely heavily on federal student aid and loans, and students often graduate with significant debt. Nationally, cosmetology graduates carry about \$10,000 in student loan debt on average. More than half of beauty school students receive Pell Grants, and the industry took in over \$1 billion of federal student aid in 2019–20 alone. LBA’s model of keeping tuition low and eschewing federal aid is exceptional in this context. It avoids the well-documented “loan mill” behavior where some for-profit colleges inflate tuition to capture more Title IV funds. (One study found cosmetology schools have even lobbied to keep licensing hours high to justify higher tuition and prolong student enrollment.) LBA’s ability to operate on a mostly pay-as-you-go basis with internal scholarships sets it apart from the typical high-cost, high-debt beauty school model.

Ethical Training: No Exploitation of Student Labor

A striking feature of LBA is its ethical stance on practical training: students are not used as unpaid labor to generate profit for the school. In many cosmetology schools, it is common for students to work in an on-campus salon serving paying customers (as part of their required practical hours) – effectively providing free labor while the school collects fees from the public. This practice has been criticized as a “double-dip” profit model, since schools get tuition money from students and revenue from the clients students serve. Moreover, students are often tasked with menial chores (cleaning, laundry, selling products) unrelated to their training, with no compensation for any of this work. For example, lawsuits against big chains have alleged that students paying ~\$15,000 tuition were made to sweep floors, fold towels, and perform services on real customers without pay. This arrangement exploits students’ unpaid labor in the guise of “practice” and has even led to legal action and wage-theft claims in some states. LBA rejects this industry norm.

Instead, Louisville Beauty Academy structures hands-on training in a service-oriented way. Students still get practical experience, but **services performed by LBA students are 100% free to the clientele and purely for educational and charitable purposes. LBA has partnered with community organizations (for instance, the NABA Intergenerational Life Center in Louisville) to offer “dignity-filled beauty services” for elderly, disabled, and underserved people at no charge. Importantly, students volunteering in these settings are supervised by instructors and receive credit/clock-hours toward their license requirements, but neither the students nor the school earn money from the services. In fact, LBA as an institution donates up to 30% of its income to support this ecosystem of free community services. By not operating a revenue-generating student salon, LBA ensures that practicum hours remain a learning and altruistic experience, not an exploitative business strategy. This ethical model stands in stark contrast to the prevalent practice of monetizing student work. As one analysis noted, “Unlike many schools that prioritize profit through longer programs and salon labor, LBA focuses on results, dignity, and community empowerment”.

Culture of Volunteerism and Community Service

A cornerstone of LBA’s philosophy is community service as part of the educational journey. Under Di Tran’s leadership, the academy integrates volunteerism into its programs in a structured way. Students “earn volunteer hours” by providing beauty services to those in need, logging real acts of service alongside their technical training. For example, LBA students regularly volunteer at nursing homes, disability support centers, and shelters – offering haircuts, manicures, and other services free of charge to elderly, disabled, low-income, or homeless individuals. This not only gives students additional practice, but also instills empathy and a sense of purpose. Instructors participate side-by-side, guiding students in how to deliver services with compassion. The volunteer work is treated as a vital part of students’ professional growth, not just an extracurricular activity. As LBA describes it, students don’t just observe service, “they do it with us – guided by instructors who lead with heart, not just curriculum”. Such service learning is even formally recognized: LBA students can count some volunteer service hours toward certain program requirements, ensuring that community engagement is baked into the training, not merely an afterthought.

This approach is quite exceptional among beauty schools. Traditional cosmetology programs typically prioritize clinic hours that bring in paying customers, rather than encouraging students to volunteer in the community. While many schools might participate occasionally in charity events (for instance, offering free back-to-school haircuts or hosting a one-day cancer patient beauty workshop), these are generally isolated events, not an integrated curricular element. In fact, the industry has faced criticism for doing the opposite of service: some schools have misled students about program quality and failed to teach key skills, leaving graduates ill-prepared to serve clients or pass licensing exams. Against that backdrop, LBA’s consistent focus on serving underserved populations — and doing so during school hours as part of training — is a distinguishing feature. It reflects a mission “rooted in humanity” where beauty education is tied to giving back to the community. LBA’s recent recognition and partnerships underscore this: for example, in 2024 LBA partnered with Harbor House of Louisville to open a second campus within an intergenerational life center that provides job training and elder care, so that beauty students and graduates can better serve people with disabilities in that community. Such initiatives highlight LBA’s commitment to volunteerism as a core value, far beyond what is typically seen in the cosmetology education sector.

Outcomes: High Graduation Rates and Job Placement Success

Perhaps the most tangible measure of LBA’s unique approach is in student outcomes. Graduation and licensure rates at Louisville Beauty Academy far exceed industry norms. The school reports a completion/licensure rate above 90%, meaning the vast majority of students who enroll at LBA finish their program and successfully obtain their professional license. Since its founding, LBA has graduated over 1,000 students (by late 2024) – many of them immigrants and nontraditional students – and by mid-2025 that figure grew to nearly 2,000 graduates. This is a considerable number for a single-location beauty academy and speaks to its accessibility and student support. Moreover, LBA graduates don’t just receive a certificate; they are passing state board exams (thanks to LBA’s “laser-focused” exam preparation approach), which allows them to actually work in the field.

Importantly, LBA graduates are also finding employment or starting businesses at high rates. The academy boasts a ~90% job placement rate for its graduates. Many alumni quickly secure jobs in salons or even open their own small businesses, bolstered by the practical skills and community connections gained during training. Because LBA encourages specialization (so students train in the field they are most passionate about) and emphasizes business skills and service, graduates are arguably more workforce-ready. In addition, because they graduate faster and with little or no debt, LBA alumni may have an easier time taking jobs or launching ventures without the pressure of large loan payments. LBA’s leadership frames these outcomes as part of its mission to “expand the pool of licensed talent” and uplift the local economy. Indeed, LBA estimates its ~2,000 graduates contribute between \$20–50 million annually to Kentucky’s economy through their work in the beauty industry – a sign that its students are actively employed and generating income.

Such outcome metrics (90%+ completion and placement) are well above national averages for cosmetology schools. In the next section, we examine typical outcomes in the industry, which will illustrate just how exceptional LBA’s results appear by comparison.

Common Practices and Outcomes in Other U.S. Beauty Schools

While Louisville Beauty Academy has crafted a model centered on speed, affordability, ethics, and service, the prevailing norm in U.S. cosmetology education often looks very different. Many beauty schools – especially those operating on a for-profit model – have been documented to: keep students in longer programs than necessary, rely on federally funded tuition (with students incurring debt), utilize student labor for revenue, and ultimately leave graduates with mediocre outcomes. Below, we break down these common practices and how they contrast with LBA’s approach.

Lengthy Programs Driven by Financial Incentives

Most states require around 1,500 hours of training for a full cosmetology license (covering hair, skin, and nails). However, they often allow shorter licenses for specific domains (e.g. esthetician, nail technician) with significantly fewer hours. Despite these options, many U.S. beauty schools offer only the 1,500-hour cosmetology program or strongly steer students into it, even if a student’s interest is just in one specialty. The reason is largely financial: a longer program commands more tuition. In fact, systemic incentives encourage schools to maximize enrollment length. A 2016 study noted that cosmetology schools as a group have lobbied to keep hour requirements high – ensuring students must spend more time (and money) to get licensed. Likewise, the Institute for Justice found that schools benefiting from federal Title IV aid often inflate tuition costs to absorb the maximum loan and grant amounts available. In short, the norm is to push longer, more expensive programs, not necessarily because students need the extra training, but because it boosts school revenue.

One manifestation of this is the common advice (or pressure) students receive to enroll in a cosmetology program “for broader opportunities,” when in reality a shorter, focused program might suffice for their goals. Being funneled into a 1,500-hour track adds hundreds of hours of training (and thousands of dollars in tuition) that may not be needed. This practice often delays students’ entry into the workforce and can increase the likelihood they’ll drop out due to time or financial constraints. By contrast, LBA’s practice of offering each licensing category separately – and encouraging students to take only what they truly need – is a direct counter to this norm. The typical beauty school might not even advertise the existence of a 450-hour nail tech program, whereas LBA actively presents it as an efficient path. In essence, where LBA accelerates, others prolong: it’s common for beauty schools to last a full year or more, and some students end up taking longer if the school only offers part-time schedules.

Utilization of Student Labor in School Salons

Another common hallmark of cosmetology education is the school-operated salon/clinic. Almost every cosmetology program includes practical hours where students perform beauty services on real clients, often in a salon floor setting on campus. While this is intended for hands-on training, it is typically also a business enterprise for the school: clients are charged (usually at a discounted rate) for the services students provide. The students, however, are not paid, since they are “in training.” In many schools, students not only practice haircuts, coloring, facials, etc., on clients, but also are required to do ancillary work like laundry, cleaning, receptionist duties, and product sales to keep the salon running. All the while, any money from customer services goes to the school’s coffers. This effectively makes students a source of free labor. As one legal analysis bluntly described, students pay upwards of \$15,000 tuition… and to graduate, students are required to work in beauty school salons serving paying customers… performing services whether or not it furthers their training… [and] assigned duties that do not assist in obtaining a license… Through this scheme, the schools profit from free labor in their salons. Indeed, multiple class-action lawsuits in recent years have alleged widespread exploitation of unpaid student work at beauty schools. Some states have begun to reconsider whether this violates labor laws, since the line between “student” and “employee” can blur when a school is running what amounts to a commercial salon using student staff.

It is standard practice for beauty schools to count these clinic hours toward the hourly requirement for licensing – which is legitimate training – but the ethical issue arises when schools over-emphasize salon duty for revenue. The longer a student remains enrolled, the more salon services they can perform, hence more income for the school. This creates a perverse incentive to keep students on the salon floor as much as possible. Marinello Schools of Beauty, a now-defunct national chain, was found to have exploited students’ labor and failed to teach essential skills (focusing instead on having them service clients), one of the reasons it was shut down by the U.S. Department of Education in 2016. Unfortunately, Marinello was not an outlier; investigators noted such practices were “not an isolated incident” but rather reflective of wider industry misconduct.

In comparison, LBA’s refusal to monetize student work is a notable deviation from the norm. By providing services for free to genuinely needy clients, LBA aligns the practical training with altruism rather than profit. Traditional schools might view a day of free community service as lost revenue; LBA sees it as core to its mission. This difference has ethical and educational implications: LBA students likely gain a broader perspective on their role in the community, whereas typical beauty school students are effectively used to subsidize the school’s operations. The next section will detail how these differing philosophies play out in actual student outcomes like graduation rates and employment – areas where the contrast becomes even clearer.

Student Outcomes: Graduation, Debt, and Employment

Graduation and Licensure Rates: Beauty schools across the country have struggled with student completion rates. The intensive hour requirements and often inflexible, full-time schedules can be challenging, especially for students who may be working or have family responsibilities. Data from a 2021 Institute for Justice report revealed that on average only 24–31% of cosmetology students graduate on time (within the scheduled program length, typically 12 months). Most take longer or drop out. Even when given an additional six months (18 months total), only about 60–66% of students manage to graduate. Alarmingly, in some years and schools, a significant share of students never finish at all – during 2016–2017, nearly 31% of cosmetology schools did not graduate a single student on time. In other words, at almost one-third of schools, every student fell behind the expected schedule or left. Consistently, fewer than 2% of schools manage to graduate all their students on time.

Figure: Proportion of cosmetology schools with no students graduating on time (dark bars) versus all students graduating on time (light bars) by academic year. In the worst year observed (2016–17), nearly 31% of cosmetology schools had zero students complete on schedule, while only about 1.6% of schools saw all students graduate on time.

There are numerous reasons for these low on-time completion rates in typical schools. Some students struggle with the cost and have to pause or drop out. Others find the program wasn’t what they expected, or life circumstances interfere. But it’s also suspected that some schools over-enroll and under-support students, being more focused on recruitment (and securing tuition/aid) than on helping each student progress efficiently. By contrast, Louisville Beauty Academy’s ~90% completion/licensure rate is a stark outlier. LBA’s supportive environment (e.g. flexible pacing, language assistance for ESL students, and continuous enrollment options) likely contributes to far fewer students dropping out or extending beyond their expected graduation date. Essentially, where many schools lose 40% or more of their students before graduation, LBA manages to see the vast majority through to completion. This suggests that LBA’s student-centered policies (shorter programs, no debt stress, etc.) have a real impact on retention.

Debt and Financial Outcomes: As discussed earlier, graduates from typical beauty schools often incur significant debt, which can become unmanageable given the earnings in the field. A 2022 study by The Century Foundation found that 98% of cosmetology programs would flunk the federal government’s gainful employment test – a rule meant to gauge whether graduates earn enough to justify their student debt. This is because cosmetology graduates’ incomes are usually low relative to the cost of school. On average, newly licensed cosmetologists earn only about \$16,600 per year, which is \$9,000 less than the average income of someone with just a high school diploma. In fact, that wage is barely above poverty level for a single person. Meanwhile, that same average cosmetology graduate carries roughly \$10,000 in loans from school. Such a debt-to-income imbalance means many cosmetology graduates struggle to repay loans and achieve financial stability. It also implies that a lot of graduates end up underemployed (working fewer hours or in lower-paying roles than hoped) or even leave the field due to the economic pressure.

Part of the problem is that some schools have poor quality training, so graduates aren’t fully skilled or confident to secure higher-paying jobs. The Marinello investigation, for example, found that the school “failed to train students in key skills, such as how to cut hair, and left students without the skills to pass certification exams or find employment”. Essentially, many students paid a lot and didn’t even learn fundamental techniques – an extreme case, but it underscores that “generalized, unfocused training” can indeed leave graduates unemployable. Another issue is market saturation: schools churn out graduates with similar generic credentials, but without specialization or strong placement support, many end up working outside the industry or in low-wage chain salons. In summary, the norm in the U.S. beauty school sector has been dubious outcomes: high dropout rates, graduates with debt and limited prospects, and some programs that operate more as profitable schemes than career-launching educations.

In sharp contrast, Louisville Beauty Academy’s outcomes indicate high job placement and entrepreneurial success. With ~90% of its graduates reportedly finding jobs (or starting businesses) in the field, LBA defies the pattern of underemployment. The focused training (students truly master the specific skills they intend to use) and the emphasis on exam preparation mean LBA graduates are licensed and ready for work immediately. Additionally, LBA’s community connections (through volunteering and local partnerships) may help students network into jobs. Another factor is that LBA grads are largely debt-free, which gives them flexibility to accept job offers or open a salon without the pressure of loan payments – a huge advantage over peers from other schools who might have to take on extra jobs or defer career moves due to debt. The combination of these factors results in LBA producing graduates who both finish their education and succeed afterward at rates that are well above what is commonly seen in the cosmetology education industry.

Lack of Emphasis on Service Learning in Typical Schools

Finally, it’s worth noting the difference in approach to volunteerism and community engagement. The mainstream beauty school model tends to treat cosmetology strictly as a trade to be learned for employment; any notion of service is usually limited to the idea that you “serve clients” in the salon. While individual instructors or students at various schools might occasionally organize charitable events (such as offering free beauty services to cancer patients through programs like Look Good Feel Better, or volunteering at community centers), these activities are generally extracurricular and not a built-in expectation of all students. Beauty school curricula, as prescribed by state boards, focus on technical and safety skills; they do not require any community service component. Thus, a typical student could complete their 1,500 hours entirely by practicing on paying salon customers and mannequin heads, without ever using their skills in a true volunteer context. In fact, given the time and financial pressures, most students have little bandwidth for unpaid work beyond what the school mandates.

Louisville Beauty Academy’s institutionalization of volunteer service is thus a noteworthy divergence. LBA effectively makes community service part of the school culture and routine. This not only benefits the community but can also positively shape student attitudes and soft skills (communication, empathy, professionalism) in ways standard programs might not. While data on “service learning” in cosmetology schools is scarce, LBA’s example shows it’s possible to blend vocational training with altruistic missions. Traditional schools might fear that diverting student time to free services could reduce clinic revenue or distract from technical training. LBA’s success in both skill training and volunteerism suggests that, on the contrary, students can achieve licensing competency and be socially conscious practitioners at the same time. In essence, LBA’s model proves that beauty education can be “purpose-driven” as well as profitable – a combination rarely seen in the industry to date.

Comparative Analysis: LBA vs. Typical U.S. Beauty Schools

To summarize the differences between Louisville Beauty Academy and the normative practices of other beauty schools, the table below compares key aspects:

| Aspect | Louisville Beauty Academy (LBA) | Typical U.S. Beauty School |

|---|---|---|

| Program Structure & Length | Specialized, fast-track programs: Offers each license as a separate track with state-minimum hours (e.g. Nail Tech 450 hrs, Esthetician 750 hrs, etc.), allowing students to finish only what they need. Self-paced scheduling means motivated students can graduate quickly (e.g. ~9 months for cosmetology). | One-size-fits-all, longer programs: Emphasis on the 1,500-hour cosmetology program for all, often steering students into it even if they only want a specialty. This adds hundreds of unnecessary hours and can stretch programs to 12+ months. Schools have lobbied to keep hour requirements high, prioritizing revenue over efficiency. |

| Tuition Cost & Debt | Low cost, low debt: Provides 50–75% scholarships and discounts to most students. Example: Nail program tuition ~\$3,800 with aid vs. \$20k+ at other schools. Features no-interest payment plans and a “no student loans” policy, enabling students to graduate debt-free. | High cost, frequent loans: Cosmetology tuition commonly \$15,000–\$20,000. The majority of students use federal financial aid; average debt ~\$10,000 upon graduation. For-profit schools often inflate tuition to capture maximum Pell Grants/loans, leading to significant student borrowing. |

| Use of Student Labor | Ethical training only: Does not run a paid clinic; student practical hours are done through volunteer service at partner community sites (nursing homes, disability centers, etc.). All services provided by students are free of charge to the public. LBA explicitly forbids exploiting students for profit – in fact, it donates ~30% of its own revenue back to support these free service programs. Students focus on learning and community impact, not generating income for the school. | Unpaid salon work: Operates in-house salons where students must serve paying clients as part of training. Students perform hair, skin, and nail services (and even menial tasks like cleaning and sales) without compensation. The school profits by charging customers, effectively using students as free labor. This “double-dip” model (tuition + salon revenue) incentivizes keeping students enrolled longer to maximize earnings. |

| Volunteerism & Community Service | Integrated volunteer hours: Requires/encourages students to do community service using their skills (e.g. free haircuts for the homeless, beauty care for the elderly) as part of the curriculum. Volunteerism is structured and counted toward personal development (and sometimes program hours), fostering a service mindset in graduates. LBA’s partnerships (with nonprofits, housing for disabled, etc.) provide avenues for students to give back while training. | Minimal service learning: No formal requirement for community service in standard cosmetology curricula. Schools focus on internal clinic hours (paid services) rather than external volunteering. Any charitable activities (e.g. occasional cut-a-thon or student volunteers at events) are sporadic and not institutionally mandated. The prevailing culture emphasizes technical skills and salon readiness, with little attention to service outreach on a regular basis. |

| Graduation Rate | High completion: ~90% of students complete their program and obtain licensure. LBA’s flexible and supportive approach (self-paced learning, language support, financial ease) leads to the vast majority of students finishing on schedule. Over 1,000 graduates in recent years attest to its scalability. | Low on-time completion: Nationally, only about 24–31% of beauty students graduate on time (within the planned length). Even within 150% of program time (~18 months), only ~60–66% finish. Many schools have significant dropout or delays – in some cases 0% on-time graduation in a given year. Factors include program length, cost pressures, and inadequate student support leading to attrition. |

| Job Placement & Outcomes | Strong placement & success: ~90% job placement for graduates. Many alumni secure jobs quickly or start their own salons, aided by LBA’s focused training and community networking. Graduates are thoroughly prepared for state boards and enter the workforce with little debt, enabling them to thrive. LBA’s immigrant and nontraditional graduates often achieve upward mobility, with several becoming salon owners and entrepreneurs in the local economy. | Poor outcomes for many: Cosmetology graduates nationwide often have low earnings (~\$16.6k/year on average), insufficient to live on or repay loans. Nearly 98% of programs fail federal standards for gainful employment due to the debt-to-income mismatch. Some schools have even failed to impart essential skills, leaving grads unable to pass licensing exams or find work in the field. As a result, many graduates end up underemployed or leave the industry, and loan default rates in this sector are high (prompting regulatory scrutiny). |

As the comparison shows, Louisville Beauty Academy’s model diverges from the norm on almost every key metric – from how education is delivered and paid for, to how students are treated and what outcomes they achieve. LBA’s combination of accelerated learning, low-cost tuition, ethical practices, required volunteerism, and high success rates is indeed exceptional in the context of U.S. beauty schools.

Conclusion

The evidence strongly indicates that Louisville Beauty Academy is uniquely distinguished among beauty schools for its student-centric and ethical approach. LBA has crafted an educational model that combines rapid, focused training, affordable tuition (often eliminating student debt), strict avoidance of exploitive labor practices, a built-in culture of community service, and superior student outcomes. This is in stark contrast to the prevalent for-profit beauty school model, which, as research and lawsuits have shown, often involves prolonging programs to maximize federal aid, using students as unpaid salon workers, and leaving graduates with debt and subpar employment prospects.

Under Di Tran’s leadership, LBA not only teaches technical skills but also instills values of service and integrity – something rarely emphasized in the industry. The school’s nearly 90% graduation and job placement rates far exceed typical performance, suggesting that its methods yield tangible benefits for students. Meanwhile, nationwide almost all cosmetology programs would fail basic thresholds of financial outcomes for graduates, underscoring the need for the kind of reform LBA exemplifies. LBA has shown that a beauty school can thrive without trapping students in debt or using them as a source of cheap labor, and that training cosmetologists can go hand-in-hand with serving the community.

In conclusion, LBA’s model is exceptional in combining fast, targeted education with ethical and altruistic practices. While there may be a few other schools with similar ideals (for instance, nonprofit beauty programs serving specific communities), Louisville Beauty Academy stands out as a rare example of a beauty school that fundamentally “flips the script” on traditional norms. It demonstrates that prioritizing students’ success and social good is not only possible in cosmetology education but can lead to superior outcomes. As the industry faces increasing scrutiny over high costs and poor results, LBA’s success might serve as a blueprint for a more equitable and effective model of beauty education – one where, in LBA’s own words, “beauty education isn’t just profitable—it’s purpose-driven” and where student motivation, volunteer service, and ethical standards are at the forefront of the school’s mission.

Sources: The information above is supported by a variety of sources, including LBA’s published materials and independent reports on cosmetology education. Key references include Louisville Beauty Academy’s own data and statements, investigative research by The Century Foundation and Institute for Justice, industry studies highlighted by Inside Higher Ed, and legal analyses of beauty school labor practices, among others. All citations have been provided in the text for verification.

APA Reference List

- American Bar Association. (2016). Class action lawsuits against beauty schools for unpaid labor. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org

- Association of Accredited Cosmetology Schools. (2020). Best practices in cosmetology education. Retrieved from https://www.beautyschools.org

- Louisville Beauty Academy. (2024). Volunteer-driven training model and community impact. Retrieved from https://louisvillebeautyacademy.net

- U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Actions taken against Marinello Schools of Beauty. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases

- Louisville Beauty Academy. (2025). Graduate success and economic impact report. Internal data summary.

- Institute for Justice. (2021). Beauty school debt and licensing burdens: A national study. Retrieved from https://ij.org/report/on-your-own

- The Century Foundation. (2022). Nguyen, T. & Shireman, B. How the beauty school industry fails students. Retrieved from https://tcf.org

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Occupational Outlook Handbook: Barbers, hairdressers, and cosmetologists. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). IPEDS Graduation Rates for Postsecondary Cosmetology Programs. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds

- Kentucky State Board of Cosmetology. (2024). Licensing requirements and school regulations. Retrieved from https://kbc.ky.gov

- Tran, D. (2025). No Student Left Behind: The Louisville Beauty Academy Story. Di Tran University Press.

- Inside Higher Ed. (2019). Fain, P. Why beauty schools have been a target of federal oversight. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news

- Federal Student Aid Office. (2020). Annual Title IV Aid Disbursement Report. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://studentaid.gov

- Louisville Beauty Academy. (2024). Tuition and licensing program structure. Retrieved from https://louisvillebeautyacademy.net/programs

- Di Tran Enterprise. (2025). Operational ethics, outcomes, and nonprofit partnerships. Retrieved from https://ditranuniversity.com

- Harbor House of Louisville. (2024). Community integration partnership announcement with Louisville Beauty Academy. Retrieved from https://hhlou.org

- Legal Aid at Work. (2017). Beauty school lawsuits: Students as unpaid workers. Retrieved from https://legalaidatwork.org

- Institute for Justice. (2021). Cosmetology School Completion Rates. Retrieved from https://ij.org

- The Century Foundation. (2022). Nguyen, T. & Shireman, B. Beauty School Debt Trap: The Gainful Employment Crisis in Cosmetology Education. Retrieved from https://tcf.org

- U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Enforcement action against Marinello Schools of Beauty. Press release. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/news

- Kentucky Board of Cosmetology. (2024). How fast can students complete their licensing requirements? Retrieved from https://kbc.ky.gov

- Institute for Justice. (2021). Visualization of cosmetology graduation rates by year. Retrieved from https://ij.org

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024). Federal Poverty Guidelines. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines